Considering that the rise of barefoot shoes is a fairly recent phenomenon, it might be tempting to think the idea that shoes should respect the natural shape of the foot is a new, radical concept. In reality, people have been calling for healthier footwear options for many years, long before even Edward Munson designed his anatomical military boot last in 1912.

As fashion is in a constant state of flux, certain periods of time have been far healthier for the foot than others. As can seen today, some fashion designers have been leaning heavily into foot-shaped toe boxes, so I guess that means they’re on trend at the moment. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, you had broad-toe styles such as the cow’s mouth or duckbill shoe. But narrow, pointed toe boxes have remained popular throughout many points in history, much to the detriment of the wearer’s feet.

Admittedly, my knowledge of footwear history is pretty limited. Somewhere down the line I’d picked up the notion that shoes made “back in the day” were typically healthier and more likely to be made to the customer’s measurements, and that the problems plaguing the footwear industry today were mainly due to the mass-production of readymade shoes. After spending some time reading the books to be discussed in this multi-part series, clearly history is not quite that simple.

Petrus Camper

Back in 1781, Dutch anatomist Petrus Camper wrote a short essay entitled “Verhandeling over den besten schoen” (“On the Best Form of Shoe”). He initially undertook to write it in a lighthearted attempt to prove to his students that just about anything could be made to sound interesting—even a seemingly mundane object like a shoe.

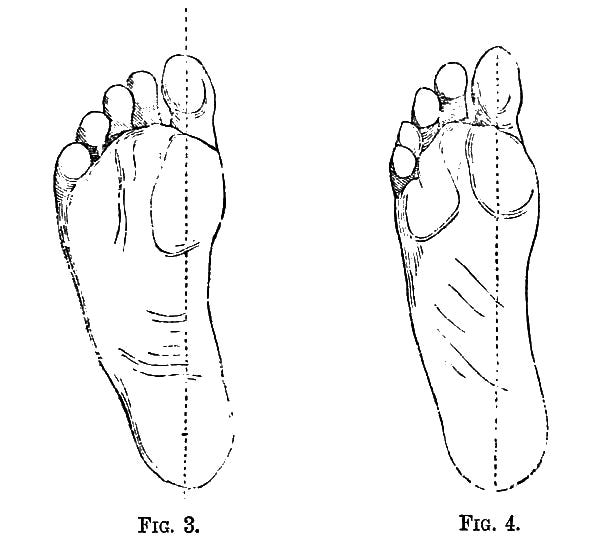

His pamphlet, however, turned into an unflinching critique of the footwear being produced in his day. At the time, it was common for shoes to be made on “straight lasts” that were symmetrical and could be worn on either foot (right and left lasts were not widely used until the mid-1800s). It’s not hard to see why this could be quite damaging to the foot:

“The Last on which the shoe is made having to serve both feet, is, nevertheless. always shaped in such a manner that the two sides are nearly alike, so that the great toe, strong as it is, is forced towards the others.”

According to Camper, most shoemakers at the time lacked a true understanding of human anatomy and had a faulty method for measuring the feet. They took their measurements while the foot was at rest and made their best guess as to how long the shoe should be. Because the foot lengthens while walking, this often resulted in shoes that were way too short. To remedy this, Camper suggested footwear should be at least 1/2 - 1 inch longer than the foot.

He was equally critical of the upper classes for vainly forcing their feet into tiny shoes in an attempt to look dainty. In Camper’s words, “we suffer cruelly when our shoes are too narrow” and recommended that soles should be “as broad as possible.”

Camper did not neglect to mention the harm that high heels can cause, like the calf muscles shortening so much that being barefoot or wearing low heels becomes quite uncomfortable. He pointed out that high heels create excess curvature in the spine and can wreak havoc on women’s bodies during pregnancy, possibly leading to complications during childbirth:

“I am intimately persuaded that the custom of wearing high heels, solely intended to give height to the figure, especially of the fair sex, is the cause of many difficult labours, more particularly among the wealthy. Women in the lower ranks of life do not suffer in the same way, escaping mainly, as I apprehend, from the habit of wearing low-heeled boots and shoes.”

Interestingly, Camper noted that most stockings were too tight and further contributed to the problem, suggesting that socks be made with individual digits like gloves—which is a type of sock that has gained popularity among many barefoot shoe wearers today.

Camper called for “radical reforms” in the way shoes were being made. Although his essay generated some interest and was quickly translated into several languages, it did not immediately spark a widespread revolution in the footwear industry. Instead of saying that Camper was “ahead of his time” (because that phrase annoys me), I would point out that people tend to be fairly slow in adopting new ideas, so advancement in any field is naturally a long, drawn out process—even on something as sensible as wearing shoes that don’t deform your feet.

Georg Hermann von Meyer

Georg Hermann von Meyer was a German professor of anatomy at the University of Zurich. He wrote the pamphlet “Die richtige Gestalt der Schuhe” in 1858 (which was translated into English under the delightful name “Why the Shoe Pinches”). His piece attracted a fair amount of attention, and even today you can find many references to Meyer’s work.

Like Camper, Meyer observed horrific foot deformities during his study of human anatomy and believed footwear to be the primary culprit. He reasoned that the shoe must conform to the shape of the foot, otherwise the foot will conform to the shape of the shoe due to its pliability. As he wisely stated, “The shape of the shoe has too much influence on health and comfort to be left to the dictates of fashion.”

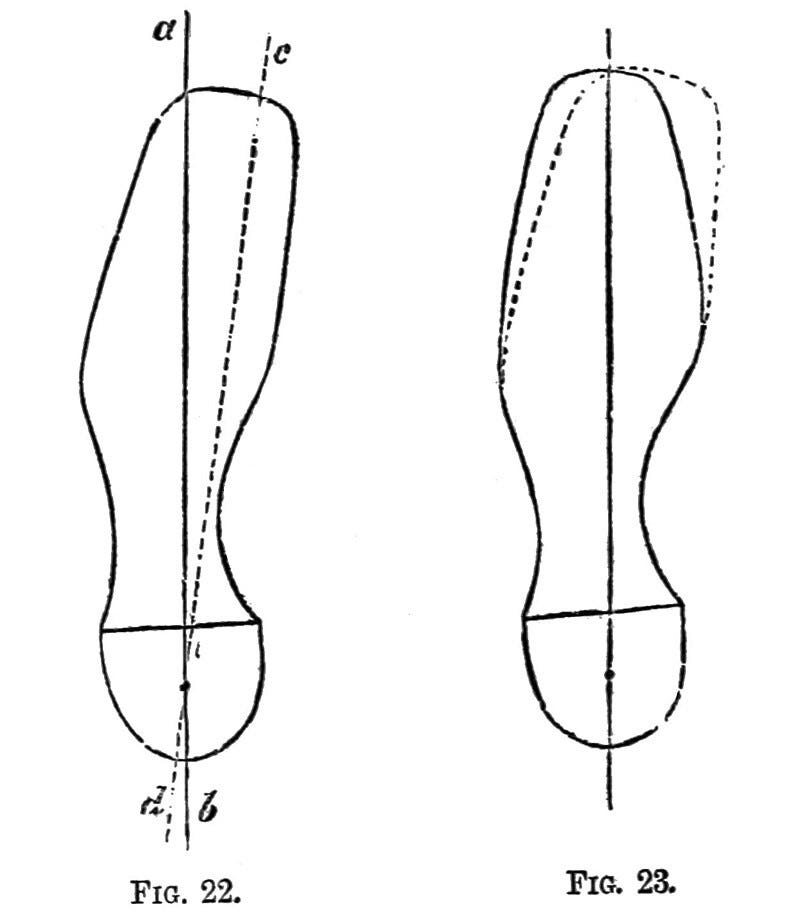

Meyer’s main area of concern was the positioning of the big toe, which was frequently forced out of alignment by wearing narrow shoes. He asserted that in a functional foot, you should be able to draw a line from the middle of the big toe straight down to the center of heel. This line is commonly referred to now as “Meyer’s line.”

Meyer took issue with shoemakers’ practice of tracing the customer’s feet to use as the basis for the sole shape. The problem Meyer had with this was that oftentimes the customer’s feet had been deformed from years of wearing improper footwear, so making a shoe from such a drawing would only exacerbate the issue.

“‘The shoe is made exactly to the foot,’ says the shoemaker, and his victim also readily consoles himself with this reflection, and attributes his long-endured infirmity of feet to every cause but the right one.”

Instead of using the customer’s foot tracing for the sole, he suggested that the shoe should follow the natural shape of a healthy foot, which would leave space for the wearer’s feet to reclaim their proper position over time. He also did not approve of tracing the customer’s feet in tight-fitting socks, which I might point out is a custom that some bespoke shoemakers still use today.

Meyer anticipated that many people would be hesitant to adopt his proposed sole shape because it looked so different from what they were used to, and this was his ready response:

“One set of people consider elegant and fashionable as equivalents. I need only remind these, that Fashion has already had many changes, and that she brings about new ones every day. It is perfectly possible, then, that she may one day take up the proposed form, and from that moment it will become elegant. A shape may come into fashion—and be thought elegant too—provided only a considerable number of persons approve of and adopt it.”

James Dowie

James Dowie was a Scottish shoemaker who began his apprenticeship in 1815. He developed an interest in human anatomy and began to realize the extent to which his lasts differed from the shape of the human foot. When he expressed this to his workers, some of them were shocked that there was any difference at all. From there, he seems to have made it his mission to bring healthier footwear to the world. It was Dowie who first arranged to have Camper’s pamphlet on footwear translated into English and published in section one of his book “The Foot and Its Covering” in 1861.

Most references to Dowie mention him only in passing for his translation of Camper, but he deserves more credit for his own contributions to the field of healthy footwear. In 1865 he wrote the book “On the Motions of the Human Feet,” where he laid out his approach to shoemaking, which can be summed up in these words: “My plan is simply to take away all hindrances to a free and perfect movement of the whole foot and ankle, and thus leave Nature to work her own cure.”

Dowie recognized that wearing hard, rigid soles restricted natural movement and he believed this to be one of the primary causes of fallen arches:

“[T]he rigid sole of the boot checks, and not unfrequently wholly restrains, the free play of both the external and internal machinery of the arch, thereby producing atrophy and general weakness… at every step in walking, the under-side of the arch of the foot receives a stroke, as if this continuous hammering was purposely intended to force up the keystone, thereby bringing the whole architectural structure down so as to form a flat foot!”

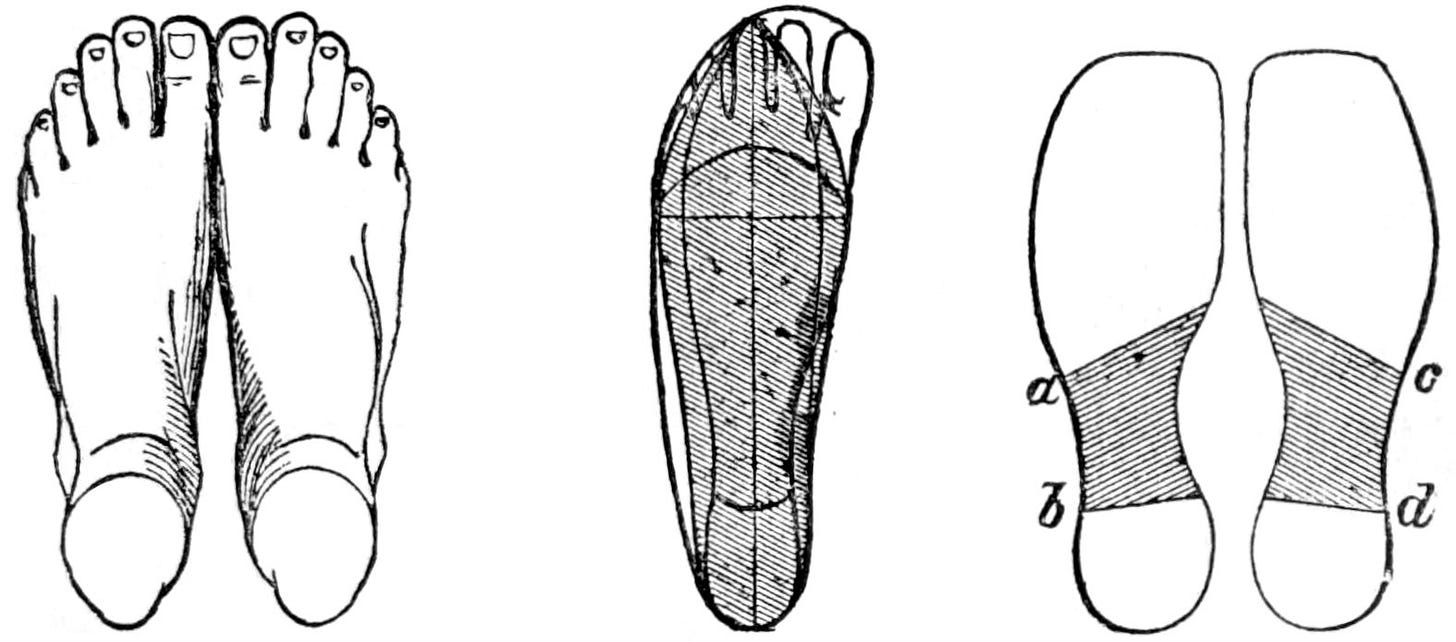

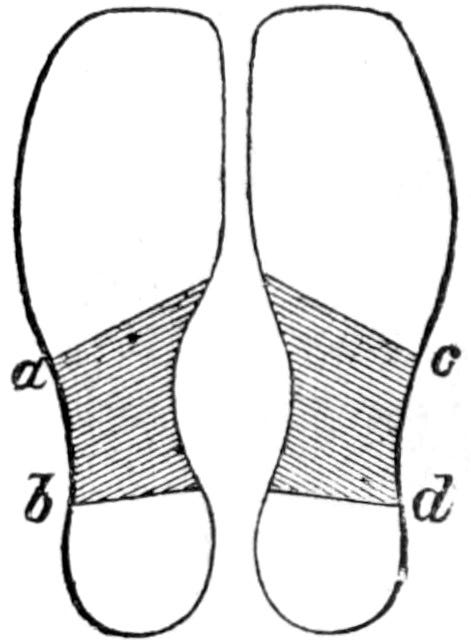

To fix this, he invented a type of flexible soling leather he termed “elasticated leather” to help preserve the health of the arch and allow full range of motion. In the image below, you can see the sole shape Dowie used for his customers. The darkened section in the arch represents where he placed his elasticated leather.

It might be an understatement to say that Dowie was not a big fan of Hermann Meyer. He claimed shoes made using Meyer’s principles had been nicknamed “ram’s horns” due to their odd curvature, and offered his rebuttal to “Why the Shoe Pinches” at the end of his second book. He did not beat around the bush in saying:

“[T]he form of the sole which [Meyer] has designed is itself objectionable, inasmuch as it pinches the little toe, and otherwise does not correspond with the drawing of the sound foot which he himself has given. In short, Dr. Meyer must study the history of shoemaking and the internal and external anatomy of the human foot more closely, before he again commences to teach shoemakers ‘Why the Shoe Pinches.’” (On the Motions of the Human Feet, p. 63)

Though Meyer did have some useful insights on the subject, it doesn’t take a trained eye to see that the sole shape proposed by Dowie looks much more natural and pleasing than the one Meyer designed. It’s one thing to study human anatomy and natural movement; it’s quite another to be able to design footwear that doesn’t impede it.

The writings of Camper and Meyer on footwear have remained influential over the years, while figures like Dowie are largely overlooked today. In the next article in the series, I’ll introduce you to a few more individuals who should also be recognized for their efforts in advocating for healthy footwear.

Read part two here.

This is excellent. Is there a broad study on the history of footwear? Even if it isn’t from a barefoot perspective, it would be interesting.